“Did your grandparents ever tell you to look at your food as you eat? There was a reason for this. Your choices and experiences are heavily linked to what you pay attention to – and what you remember.”

Pedro Bordalo

For one week, 72 MBA and EMBA students from 22 business schools gathered at Oxford Saïd Business School for the Global Network for Advanced Management (GNAM) program on Psychology, Economic Decisions, and Financial Markets.

Five of us represented IMD – Giovanni Fersini, Victor Petrassi, Ishita Mishra, Daniel Keat, and myself – ready to explore why, despite our best intentions, we so often make irrational choices.

Opening the course, Professor of Financial Economics Pedro Bordalo reminded us that standard economics assumes people act rationally and always choose what is best for them. Cognitive economics, in contrast, recognizes that people choose what seems best, shaped by what they pay attention to and what they remember.

That idea set the tone for the week: a journey through bias, attention, and the subtle forces that shape the decisions we make, from saving for retirement to buying a coffee.

First impressions

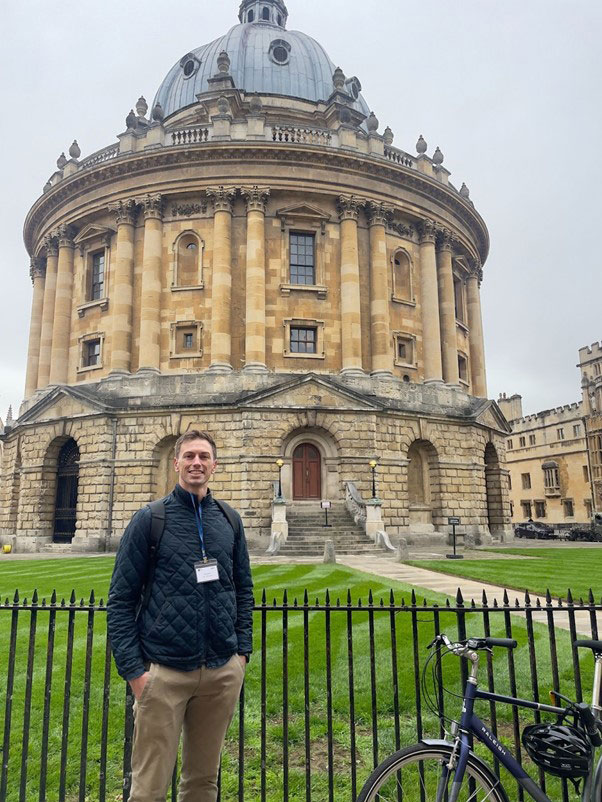

There’s something special about visiting the oldest university in the English-speaking world. Steeped in tradition with Latin inscriptions carved into stone, stained-glass windows glow through the fog, and Gothic towers peek over narrow streets.

The university area is small and walkable. So, on the second morning, our Oxford coordinator, Chris Page, organized a walking tour. It was, hands down, my favorite way to explore the city. We passed centuries of stories carved into stone: the famous Radcliffe Camera, Bodleian Library – recognizable to fans of the Harry Potter films as the Hogwarts hospital wing – and the courtyard where Oscar Wilde was once detained by Oxford police.

The towns (locals) and the gowns (students) have long had a tense relationship, with centuries of mischief and rebellion between them. Nearly a thousand years of learning and rivalry coexist here.

“Oxford isn’t a traditional university,” our guide explained. “It’s a collection of colleges, all run independently, with their own tutors, lodgings, and sports teams.”

Of the 39 Oxford colleges, some take only a handful of students. All Souls College admits no more than six a year, by invitation only, after the “world’s hardest exam” containing eccentric questions like, “If you had to lose one finger, which would you choose, and why?”

One of the unexpected highlights came through our MBAT connections. Andrew Neilson, an Oxford MBA, invited us for a private tour of Worcester College. From the outside, it didn’t look like much, but inside, we were amazed by expansive grounds with gardens, lakes, rugby fields, a chapel, a Hogwarts-esque dining hall, and more.

Inside the classroom: behavioral economics in action

At Saïd, our classes took place in lecture halls like the Nelson Mandela Theatre, and one day even inside the Museum of Natural History, among the dinosaurs. Bordalo began with a simple question: If people make decisions in their best interest, do they act rationally? This question framed our whole week.

On the first day, we covered utility theory, the idea that people weigh benefits against costs to maximize satisfaction. In theory, it makes sense; in practice, it rarely holds. When it comes to real life (like taking long-term medication), people often make inconsistent choices. We discount the value of our future selves. The present feels more real. A case study showed how small design tweaks, such as reminders or easier access to medication, can improve long-term adherence.

On the second day, we explored salience: how our attention, not our logic, drives decisions. One discussion centered on salary transparency: how reducing information asymmetry can close pay gaps but also limit flexibility for employers to reward productivity.

The third day focused on loss aversion and status quo bias: our tendency to stick with what we know. Thoughtful behavioral design can help counter this tendency. Opt-out pension plans, for example, increase savings rates simply because the default option is “yes.” We also saw how our environment steers behavior: people buy insurance when there’s risk or uncertainty, invest after bull runs, and over-purchase winter clothes when it’s cold (only to return them later).

In the final sessions, we examined overconfidence and credit cycles, how optimism can inflate bubbles and distort markets, and why every boom carries the seeds of its own correction.

These themes were familiar from IMD’s Strategic Thinking and Communications course, where we explored cognitive biases with Professor of Strategy Arnaud Chevalier, especially how overconfidence can lead to blind spots. The focus shifted from recognizing biases to understanding the research behind them, and from seeing how biases shape individual decisions to how systems can be designed for better decisions.

Beyond the lectures

Outside the classroom, the learning continued. Evenings were for connecting with students from Yale, IE, Bocconi, NUS, UBC, EGADE, UNSW, and Berkeley Haas, among others. Over pints at the King’s Arms and the Lamb & Flag (the same pub where JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis once gathered), we compared programs, career goals, and professors.

What stood out most was how quickly we connected. Despite coming from 22 schools, everyone seemed to be on the same wavelength: curious, driven, and hoping to do something meaningful. I left with new friendships and plenty of new cities to visit.

One evening we watched The Talented Mr Ripley at the Oxford Playhouse. The play, with its themes of ambition, envy, and self-deception, felt closely linked to the week’s lessons. Behavioral economics, after all, is often about the stories we tell ourselves and how easily we justify irrational choices.

Our IMD team shared an Airbnb near the city center. Mornings started with coffee runs (shout out to Nepa Coffee) and our evenings with dinners and debriefs after the day’s learning. One thing that made us laugh was the difference in punctuality. At IMD, “Swiss time” is sacred – one minute late and you’re in trouble. Oxford, by contrast, was far more… forgiving.

Reflections and gratitude

By the end of the week, we had seen how attention, memory, and small design choices can shape decisions, markets, and even societies.

I left with two main takeaways. First, that the world can be designed to make good choices easier, whether through pension opt-out settings, savings nudges, or simple reminders to take medication. Second, there is a shared language and sense of ambition between MBAs. The bonds felt genuine, regardless of schools or backgrounds.

A heartfelt thanks to Pedro Bordalo for his engaging lectures, Chris Page from Oxford Saïd for organizing the program, and the IMD MBA Office for making it all possible. And to my IMD classmates, Giovanni, Victor, Ishita, and Daniel, for representing IMD both inside and outside the classroom.

We left with new ideas, lasting friendships, and a few good stories from our time at one of the world’s oldest academic institutions.